mercredi, 10 juillet 2013

E. A. Poe scopritore di una nuova malattia dello spirito: la modernità

E. A. Poe scopritore di una nuova malattia dello spirito: la modernità

Il pubblico, specialmente il pubblico europeo, possiede una percezione parziale dell’opera di Edgar Allan Poe: la sua notorietà come scrittore di racconti del mistero e del terrore è così grande, ampliata anche dal cinema che si è impossessato di quei soggetti, da aver messo decisamente in ombra un altro aspetto della sua produzione: quella lirica.

Il pubblico, specialmente il pubblico europeo, possiede una percezione parziale dell’opera di Edgar Allan Poe: la sua notorietà come scrittore di racconti del mistero e del terrore è così grande, ampliata anche dal cinema che si è impossessato di quei soggetti, da aver messo decisamente in ombra un altro aspetto della sua produzione: quella lirica.

Leggere le poesie di Poe, immaginando di ignorare l’identità del loro autore, rappresenta una delicata e suggestiva escursione in una provincia artistica leggiadra e nostalgica, pervasa dal rimpianto della Bellezza ideale che il mondo materiale, e specialmente il mondo moderno, con le sue brutture e il suo affarismo, sembra avere irrimediabilmente compromesso; si resta un po’ sorpresi nel confrontare questo poeta delicato e un po’ platonizzante, che vibra al più lieve tocco della Bellezza, sensibile come un rametto di mimosa, al cupo autore di racconti orrorifici come La maschera della morte rossa, Il cuore rivelatore o La caduta della Casa Usher.

D’altra parte, c’è un tratto caratteristico e inconfondibile nelle liriche di Poe, dal notissimo – e forse troppo celebrato – poemetto Il Corvo (The Raven) alla raffinata, nitida poesia A Elena (To Helen), lieve come un impalpabile sogno ad occhi aperti – o magari chiusi, chi può dirlo?, l’atmosfera onirica si presta a tali giochi di specchi fra realtà e fantasia -: vogliamo dire l’attenzione alla pulizia stilistica, la sapienza della struttura lessicale e compositiva, la ricercatezza formale, simile ad un prezioso lavoro d’intarsio e di compasso; tanto da suggerire l’idea che non di poesia sentimentale si tratti, romanticamente intesa, ma di una poesia intellettualistica, razionalmente pensata ed impostata, secondo i canoni rigorosi del “secolo dei lumi”.

È un’impressione che va ridimensionata, tenendo conto che nel Poe lirico esiste un sapiente gioco di contrappunti e di armonie fra la dimensione istintiva, passionale, sentimentale – o, come lui dice, immaginativa -, e quella logica, razionale, “scientifica”; e che il pregio maggiore delle sue poesie consiste proprio nel sapiente dosaggio e nel raro equilibrio che egli riesce ad ottenere fra le ragioni del cuore e quelle della mente; nella linea, del resto, di altri grandi pre-romantici, a cominciare dal nostro Ugo Foscolo, e specialmente il Foscolo dei sonetti.

Abbiamo accennato alla “scientificità” dei procedimenti poetici di Poe, pur subordinati ad una concezione generale del fatto estetico che è d’impostazione idealistica, per la quale le cose sono le ombre o i riflessi di una realtà ulteriore, sovrannaturale o, comunque, non umana, secondo la lezione del mito platonico della caverna, ma anche dello Shakespeare dei sonetti, dei “romances” come La tempesta e di alcune struggenti e delicate commedie, a cominciare da Sogno di una notte di mezza estate (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), della quale ci siamo già occupati a suo tempo (cfr. il nostro precedente saggio Malinconia e platonismo nel Sogno d’una notte di mezza estate di Shakespeare).

Abbiamo accennato alla “scientificità” dei procedimenti poetici di Poe, pur subordinati ad una concezione generale del fatto estetico che è d’impostazione idealistica, per la quale le cose sono le ombre o i riflessi di una realtà ulteriore, sovrannaturale o, comunque, non umana, secondo la lezione del mito platonico della caverna, ma anche dello Shakespeare dei sonetti, dei “romances” come La tempesta e di alcune struggenti e delicate commedie, a cominciare da Sogno di una notte di mezza estate (A Midsummer Night’s Dream), della quale ci siamo già occupati a suo tempo (cfr. il nostro precedente saggio Malinconia e platonismo nel Sogno d’una notte di mezza estate di Shakespeare).

Ebbene, il rapporto con la scienza è un’altra preziosa chiave di lettura per accostarsi alla produzione lirica di Poe. Egli non è nemico della scienza, anche se, sulla scia di altri grandi lirici anglosassoni, in particolare del “visionario” William Blake, le rimprovera aspramente di aver gettato un’ombra desolata sul mondo, strappando il velo della poesia e imbruttendo la realtà, ingrigendo gli orizzonti della vita; ma tale rimprovero non è rivolto alla scienza in quanto tale, per la quale, anzi, egli nutre un vivo e sincero interesse e al cui metodo logico ritiene che anche il poeta debba attingere, per non parlare del prosatore (e si pensi ai suoi racconti di genere investigativo, come I delitti della Rue Morgue, caratterizzati da un rigoroso impianto razionale e deduttivo); bensì alla scienza presuntuosa e arrogante, in definitiva allo scientismo, che pretende di assolutizzare il proprio sapere e di ridurre al rango di saperi di seconda scelta quelli propri alle altre forme di conoscenza del reale, a cominciare dall’arte medesima.

Poe, dunque, non rifiuta la scienza in se stessa, così come, si potrebbe aggiungere, non rifiuta la modernità in quanto tale; ne rifiuta semmai la bruttezza, il cinismo, l’utilitarismo esasperato, il produttivismo cieco, il materialismo grossolano, la pretesa totalizzante a livello estetico, etico e filosofico; rifiuto deciso, intransigente, donchisciottesco, se si vuole, e quindi ingenuo e velleitario, ma non per questo meno sincero, non per questo meno sofferto e umanamente significativo, perché testimonia la crisi e il dramma di una civiltà faustiana che si vede presa nella propria vertigine ed esita, brancolando, sull’orlo dell’abuso, a imboccare sino in fondo la strada di un “progresso” senz’anima, foriero di sempre nuove, sconvolgenti sottomissioni dell’anima alle ferree leggi del Logos calcolante e strumentale.

E che altro è, del resto, la “caduta” della Casa Usher, se non la nemesi di un progresso disumano e accecato dall’umano orgoglio, che non riconosce limiti né misura alla propria “hybris” e che pretende di farsi legge e norma infallibile e inderogabile di ogni agire umano, di ogni pensare, di ogni sentire, come se nulla vi fosse oltre a ciò che la mente razionale può accumulare, manipolando gli enti senza sosta, sovvertendo le leggi naturali, capovolgendo il giusto rapporto fra la vita e il suo insopprimibile bisogno di bellezza?

Tutto questo appare evidente nella “protesta” di Poe, ché di una autentica protesta si tratta, ora esplicita, come nei racconti, ora implicita, come nelle poesie; ma sempre si tratta di una pretesta ferma e intransigente, non tanto in nome della nostalgia del passato pre-moderno (tentazione che, peraltro, fa sovente capolino, specie nelle liriche, in particolare sotto le forme di un richiamo alla grazia impareggiabile del mondo classico), quanto piuttosto in nome di una umanità che, pur confusa e smarrita, non è disposta ad abdicare a se stessa, al proprio sentimento di ciò che è umano, ai diritti sacrosanti della “imagination”, della fantasia creatrice di bellezza.

Così sintetizza la questione Tommaso Pisanti nel suo saggio introduttivo all’opera poetica del grande scrittore americano, E. A. Poe poeta (E. A. Poe, Tutte le poesie, a cura di T. Pisanti, Roma, Newton Compton Editori, 1982, 1990, pp. 15-21):

«Già da fanciullo “mentre era azzurro tutto l’altro cielo”, Poe vide una nuvola prender forma di demone (“of a demon in my view” (“Alone”). E lungo una tale direzione si svilupperà, più tardi, la “selvaggia visionarietà di “The Haunted Palace” (Il Palazzo stregato) e – meno compatta – quella di “Dream-Land” (Terra di sogno), col terribile, soffocante senso di una duplicità e anzi ambigua e stregata “doppiezza” angelico-demonica. Perché se il “demonico” s’accumula in Poe inizialmente come per un’intensificazione della disperazione stessa, interviene e subentra poi anche una specie di contorto sadismo “dello spirito” e dell’immaginazione, che conosce le sue orge non meno di quello fisico-corporeo. Poe vede insomma la vita come divorata e spazzata via dal gigantesco “Verme trionfante” di “The Conqueror Worm”: e ne piangono gli angeli stessi, “pallid and wan”, “pallidi ed esangui”.Nell’intollerabile tensione, Poe si volgerà anche alla Vergine, invocherà Maria: in “Catholic Hymn” (corretto poi in “Hymn”), con suggestione forse dantesca o byroniana (“Don Juan”, III st. 101 ss). Naturalmente, è sempre da tener presente quanto d’impulsivo, d’immediato, quanto dell’istinto e della multilateralità dell’attore-istrione e, al limite, di mistificatorio è in Poe. Il poeta vive, “trasognato, giorni estatici” (“And all my days are trances”), dirà in “A una in Paradiso”. Certo, Poe fu “evasivo”, “disimpegnato”: ma nel senso della “immaginazione angelica”, disincarnata, indicata da Allan Tate. Il suo esplorare la surrealtà non si risolve poi infine, tuttavia, in una più sottile conoscenza d’una più globale, estesa realtà? […]

Le poesie riservano tutto un più largo spazio, rispetto ai racconti, a quella componente dell’ardore per la Beltà, a un mito d’armonie remote e perdute […]: ardore e mitopoiesi classico-platonica soffusi d’ombre orfico-pitagoriche, e con qualche finale riverbero, magari, pur sempre goticheggiante.Una componente, questa, fondamentale, che stacca comunque Poe dalla dimensione, diciamo, soltanto “gotica” e romantico-hoffmaniana per accostarlo anche al nitore d’una linea e d’una mitizzazione classico-neoclassica, alla linea di Hölderlin, di Keats, di Foscolo: come nella splendida, esemplare “To Helen” […], pubblicata già nel 1831 e poi continuamente ricesellata. […]

E a difesa dei vecchi miti e, leopardianamente, degli “ameni inganni”, anche Poe lamenta, nel sonetto “Alla scienza”, che il “progresso” abbia tutto ingrigito e livello, che la Scienza con le sue ali “grevi” (“dull”) abbia “sbalzato Diana dal suo carro” e “scacciato l’Amadriade dal bosco” e “strappato la Naiade al flutto / l’Elfo al verde prato e me stesso infine / al sogno estivo all’ombra del tamarindo”. Ma è solo un’accentuazione particolare : giacché Poe è in realtà vivamente sensibile allo sviluppo scientifico, nella misura in cui esso è, innanzi tutto, collegato con una “mind” lucido-geometrica e anche per quanto può offrire, di nuove aperture e di nuovi strumenti, all’esplorazione e all’osservazione sottilmente operate dall’occhio e dalla mente umani (e nella mente umana). Insieme al rimpianto quindi Poe ingloba in sé un attento, tenace interesse nei riguardi della lucidità dei metodi e dei procedimenti, una ferma attenzione alla rigorosità del linguaggio matematico-scientifico, al linguaggio del pensiero e delle definizioni, che possono offrirgli materiali e stimoli proprio per il lato di rigorosità e di definizione laicizzante che egli intende dare alla sua macchina stilistica. […] Si tratta, naturalmente, di un uso “strumentale” della scienza, proprio al fine di ristabilire quella riunificazione tra il sensibile e il soprasensibile che è il supremo proposito di Poe e il supremo proposito della poesia, secondo Poe: nel quale resta nettissima, s’intende, l’avversione alla scienza come pretesa sistematica di spiegazione e interpretazione puramente ed esclusivamente logico-razionale. […]

Anche se, alla base, è la “prescienza estatica” che dà il primo scatto, è all’intelletto e alla “tecnica” che tocca poi partecipare per il fattuale concretarsi della poesia. “Non vi è peggior errore che il presupporre che la vera originalità sia semplicemente questione d’impulso e d’ispirazione. Originalità è combinare in modo attento, paziente e comprensivo”. Poe è insomma tutt’altro che immerso nella totalità romantica, resta anzi legato ad eredità settecentesche, “è un razionalista del Settecento con inclinazioni occultistiche”, ha perfino scritto il Wellek. […]

Il senso della “combinazione” non deve tuttavia indurre ad eccessive, facili accuse di “cerebralismo” e “meccanicità”. Lawrence scrisse perfino che Poe “è quasi più scienziato che artista”. Ma i meccanismo che Poe mette in movimento puntano a un “effetto”, cioè a risultati: d’eccitazione e d’intensa emotività.

Poe fu insomma scopritore- può dirsi ancora, e concludendo, con Emilio Cecchi – “di una provincia che non è quella del’orrido, dell’ossessivo, ma è semplicemente la nuova provincia dell’arte d’oggi. Solo una delle nuove province, a voler precisare. E fra tentativi e approssimazioni, se si vuole. Ma è innanzi tutto in se stessa, nella sua intrinseca composizione che la poesia di Poe va riletta e ripensata: una lampeggiante associazione di “gotico”, di tradizione classicista e di inquietanti fosforescenze anticipatrici, sì, ma già “poesia” per se stesse.»

In questo senso, e sia pure forzando, ossia andando oltre, la stessa interpretazione del Cecchi, ci sembra di poter concludere che Poe, e specialmente il Poe lirico, tanto meno conosciuto, ma non meno interessante del Poe narratore, si possa considerare come lo scopritore non solo di una nuova provincia dell’arte, ma di una nuova malattia dello spirito: la modernità.

Negli stessi anni di Kierkegaard, anch’egli leva la sua voce per protestare contro il cancro della società massificata, petulante, presuntuosa, che, forte dei propri successi tecnici ed economici, pretende di imporre il suo dominio tirannico sui regni dello spirito e sui diritti inalienabili dell’io individuale. Poe, dunque, fratello in spirito di Kierkegaard: chi l’avrebbe detto? Eppure è così.

Certo, la protesta di Poe è quella di un poeta: non possiede né la forza, né il rigore del grande filosofo danese. Davanti alla bruttezza che minaccia la vita fin nelle sue intime radici, Poe non sa cercare rifugio se non nelle braccia della donna idealizzata; ed ecco le numerose donne angelicate: Elena, Elizabeth e le altre. Fragile rifugio, quale potrebbe cercare un bambino spaventato da un brutto sogno: «Io vivevo tutto solo / in un mondo di dolore, / e la mia anima ristagnava immobile, / finché la bella e gentile Eulalia non diventò mia timida sposa» («Eulalia»). Ma la vita, è altra cosa…

* * *

Tratto, col gentile consenso dell’Autore, dal sito Arianna Editrice.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : littérature, edgar allan poe, lettres, lettres américaines, littérature américaine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

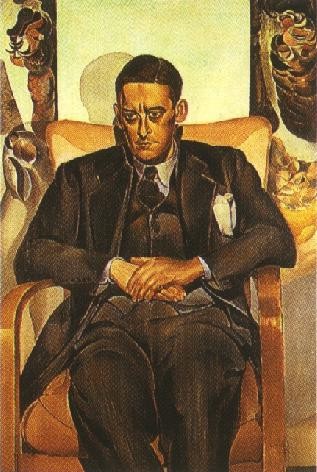

vendredi, 17 mai 2013

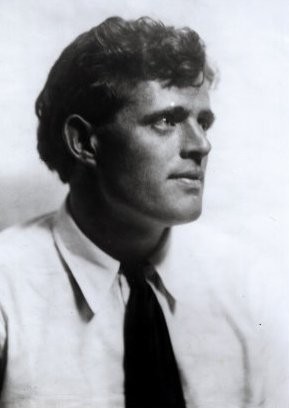

Robert E. Howard & the Heroic

Robert E. Howard & the Heroic

By Jonathan Bowden

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

The following text is a transcript by John Morgan of a lecture by Jonathan Bowden, “Robert Erwin Howard: Pulpster Extraordinaire,” given at the 26th New Right meeting in London on Saturday, April 17, 2010. The audio is available on YouTube [2].

Unfortunately, significant portions of the audio were cut off at the beginning of the second and third segments on YouTube. For the purposes of publishing this essay in the Pulp Fascism [3] collection, I also removed some 2,300 words of digressive material. If anyone has access to a complete copy of the lecture, please contact me. Also, if you have any corrections or if you can gloss the passages marked as unintelligible, please contact me at editor@counter-currents.com [4] or simply post them as comments below. If and when a complete transcript can be assembled, we will publish it here as well.

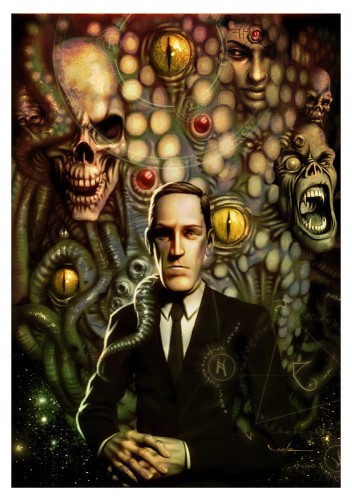

I’ll be talking about Robert Ervin Howard. A while back, I had a talk about H. P. Lovecraft, Aryan mystic, and he was one of a triumvirate of writers who wrote for a fantasy magazine called Weird Tales, a pulp magazine; they were incredibly cheaply produced magazines in the 1930s, with quite good art, graphic sort of art, printed on cheap bulk newsprint paper which was very acidic and fell apart very quickly. And yet three writers, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Ervin Howard, and Howard Phillips Lovecraft have survived and been inducted into literature. I saw in my local library that Penguin Classics, or Modern Classics, the ones with the grey covers, now include Robert Erwin Howard’s Heroes in the Wind, from Kull to Conan: The Best of Robert E. Howard as a book. Penguin Classics, you see? So it begins as a pulp, and a hundred years later it’s redesignated as literature.

Howard is a very interesting figure. He only lived 30 years. He was born in 1906 and shot himself with a revolver in the head in his car, outside his home, when he was 30 years of age. We’ll get on to that afterwards. He wrote 160 stories, and the interesting thing about these stories is that they are pre-civilized in their settings, they’re barbaric, they’re ultra-masculine stories, and they deal with many themes which have been so disprivileged from much of mainstream liberal humanist culture that they no longer exist.

Howard had a range of heroes and wrote in most popular genres. He wrote to make money, but he began as a poet, and a poetic and sort of Saturnalian disposition influenced his work and his friendship, by correspondence, with Lovecraft, and to a lesser extent, Clark Ashton Smith, throughout his life. He was of Irish descent, and he was born in a town which became a boom town in the oil booms of the early 20th century in Texas. For those of you who don’t know, Texas is enormous. England fits into Texas twelve times, and Britain, eight times. He was born in Peaster, Texas, and spent some of his early life in a town called Brownwood, a quintessentially small-town American, which is the experience of most white Americans through the settlement of Western civilization in North America. The state capital, of course, is Austin, and you have the big cities like Houston, Dallas, and Galveston.

Now, Howard hated the oil booms, and what happened. When the oil boom happened to Cross Plains, a town of about 1,200 with a mayor and so on, morphed into a large, sprawling, lawless place of about 10,000. An enormous number of prospectors and drillers and criminals and people seeking easy money, all heavily armed of course, came in to Cross Plains. The town burst out beyond its limits in all directions. Oil was discovered everywhere. Fortunes were made, and fortunes were lost.

At the time he was born, lynchings were still in vogue right across the South and the ex-Confederate states. Everyone displayed and carried weapons openly. Sometimes the Rangers, as they were called, a man alone in the sun with a rifle, was basically all you had of semi-ordered civilization. People don’t realize how, if you like, wild and open certain parts of the United States were, certainly until the 1860s, 1870s.

The psychological experience of an intuitive and sympathetic and radically imaginative young man like Howard invests the tall Texan story, and stories of prospectors and ranchers and drillers in the oil industry, and Texas Rangers and Marshals and so on, with an added piquancy. His family supported the Confederacy in a previous generation, and he was mildly descended from certain Confederate commanders.

His attitude towards life is expressed in the stories, which is why they survived. The stories are like lucid dreams. You walk straight into them, and the action begins. Most of them were dreams, and in a way, most critics believe Howard’s an oral creator. He’s in the oral, folklorist, and narrative-oriented tradition. He’s a storyteller par excellence. It’s said he wrote at night, and he used to chant the stories to himself, which of course is a very old Northern European and Nordic tradition. It’s the idea of the skald. It’s the idea that things are illuminated to you, and you speak because you hear the voice.

He had a series of masculine heroes beginning with certain Celtic and Pictish/Scotch-Irish heroes such as Bran Mak Morn and so on; Conan, the hero that he’s most associated with, whose name, of course, is abstracted from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s middle name. Howard would take from all sorts of roots, many of which related to heroic, Celtic, Indo-European elements which he imagined to exist in his own past.

He was very influenced by G. K. Chesterton’s dictum at the beginning of the 20th century that myth is the commingling of emotional reality with what is understood to be fact. If you mix together eras and peoples, but you keep the emotional truth of the substance of what we perceive their lives to have been, then you can influence the present and the future. It’s noumenal truth, as Aristotle said 2,000 years ago, the idea that certain things are artistically and emotionally true irrespective of what you think about them factually.

He was very influenced by G. K. Chesterton’s dictum at the beginning of the 20th century that myth is the commingling of emotional reality with what is understood to be fact. If you mix together eras and peoples, but you keep the emotional truth of the substance of what we perceive their lives to have been, then you can influence the present and the future. It’s noumenal truth, as Aristotle said 2,000 years ago, the idea that certain things are artistically and emotionally true irrespective of what you think about them factually.

His most famous series of stories, the Conan stories that he wrote pretty much towards the end of his life, were based upon a false yet true/factual world history, the so-called Hyborian Age that he created for himself. Maps of the Hyborian Age have been produced, and they are based upon a realistic sociology, ethnography, geological history, and a coherent view of economics. The country of Aquilonia that Conan ends up conquering at the end of the mythos is partly Britain. The Picts are partly the Scots, of course, covered in woad, barbaric, kept out by a wall, that sort of thing.

War is the dynamic of all of Howard’s fiction, and his attitude towards life was conflict-oriented. His stories are described as ultra-masculine and non-feminist stories. Unkind critics say that they’re Barbara Cartland for men, where all women are beautiful, all men are heroic, where magic works instead of science, and where force decides all social problems, and there is a degree to which the genre which he has founded, called sword and sorcery—of which one supposes J. R. R. Tolkien, an Oxford professor, is the senior representative in the 20th century—is an example of the literary and the heroic in contemporary letters. It’s interesting to notice that the early great texts of the Western civilization, Homer, Beowulf, are deeply heroic, and yet over time, the heroic imprimatur within our language and within our sensibility dips.

It’s said that boys aren’t interested in reading at school, and that 80 to 90% of those who do English literature courses in further educational colleges and universities, the tertiary sector, are women. It’s said that men don’t disprivilege literature, and it’s also said in the West that boys get bullied if they’re regarded, as Howard was when he was younger, as sissies because they read too much, and this sort of thing.

I think one of the problems is that literature that appeals to men is often not the concern of the people who run these sorts of educational establishments. If the sort of people that influenced Howard, people like Noyes, people like Robert W. Service, people like Byron, people like Kipling, people like the heroic imperialist literature of William Henley, who was the basis for Long John Silver in Treasure Island, and was a close friend of Robert Louis Stevenson, a man who could go from bonhomie to murderous rage with a click of your fingers, as Silver does in Treasure Island, of course, because he moves from extreme malevolence to a sort of Cockney paternalism in the same breath. Now, if this literature was normative much further down the social and the educational scale, one would imagine that boys and youngish men would be much more interested in literature as a whole.

Howard essentially sold stories from about the age of 20, certainly 19. He started writing when he was 9, and the interesting thing about him is that his stories are not really derivative. There are connections to enormous writers that were prominent at the time, principally Jack London, but Howard emerged fully-formed and had his own voice from the very beginning.

London’s a very interesting figure, because London’s often been associated, truthfully and yet forcefully, with the extreme Left. Trotsky, of course, wrote an introduction to his famous dystopia of American life called The Iron Heel, and yet London, as George Orwell intimated in one of his essays, was proto-fascistic, and was in many ways a Left nationalist, or even a National Bolshevik, or somebody who would be now described as a Third Positionist. London’s positions were those of socialism from the outside, but also a form of socialism, with and without quotation marks, that was Right-wing rather than Left-wing, and was both national and racial. The interesting thing about London’s discourse is the radicalism of the racialism. [. . .]

We had at the last meeting, or the meeting before last, a speaker from Croatia called Tomislav Sunić who wrote a book which I edited a long time ago, actually, called Homo Americanus: Child of the Postmodern Age. Among the very important points about that book is his recognition, as a European ex-Catholic in his case, of the Protestant fundamentalist nature of the United States. I think this is a crucial point to understand the United States. The influence of contemporary Jewry in the United States is due to the fact that it’s a Protestant fundamentalist country and many, many Americans really believe in their deep and even subconscious mind that the viewpoint that they are a self-chosen elect to rule by right, by divine imprecation, is so deep in their consciousness, the idea as Pentecostalists sing, that “we are Zion,” goes so far down that the difference between their identity and their group specificity and their militant patriotism and that of a small country in the Middle East, and people who didn’t begin to emigrate en masse into the United States until the latter stages of the 19th century, and only really began to have major socioeconomic impact, particularly culturally, in the first quarter to a third of the 20th century makes these things, to my mind, easier to understand.

Now, Protestant fundamentalism doesn’t seem to have scratched Howard very much, and yet one of his heroes is a Puritan called Solomon Kane, and Solomon Kane, who comes between Bran Mak Morn, Kull, and Conan, is in some ways his first major hero. Solomon Kane is very, very interesting because he’s one of these Protestant extremists of the 1620s—well, they’re set before—but that’s when the movement comes to power in the Cromwellian Interregnum in England, and yet stretches way back into the previous century, and yet in a strange way he’s an outsider, even in that movement.

Kane dresses all in black with a little white sort of a bib round his neck. He’s extraordinarily heavily armed, as most of the Puritans were, had a sword on either side, had pistols in the belts, had a knife in the boot, because you were fighting for the Lord, you see! “I am the flail of the Lord.” They had these endless quotes, largely from the Old Testament, but to a degree from elements of the New, which they would roll out on occasions when they had to justify what they were about to do, and that their instincts wanted to do, in a way that nothing could restrain them.

There’s a famous moment in Northern Ireland, when James Callaghan was Northern Irish Secretary under Wilson in the late 1960s, slightly sympathetic to Social Democratic, Catholic nationalism in Northern Ireland, as part of the local movement was then, but in a very moderate way, and then said in a concerned and perplexed way to the Reverend Ian Paisley, who softened a bit as he’s got older, and in turn wanted to be Prime Minister of Northern Ireland before he died, he said to Paisley that, “But we’re all the children of God, Reverend,” and Paisley said, “No! Nooooo!” He said, “We are the children of wrath!”

And that is the attitude of those Puritan extremists, loyal to the Old Testament in many ways. Men of a sort of always implacable fury, and elements of their dictatorship, under Cromwell of course, were increasingly maniacal. The banning of Shakespeare, our greatest writer. When an English national revolutionary movement bans the country’s greatest-ever writer, you do begin to think there’s something slightly wrong, don’t you, no? Similarly, the flogging of actors under the New Model Army in Newcastle for performing Shakespeare, these were the latter stages, these were the Buddhas of Bamiyan moments, weren’t they really, of these English revolutionaries of the 1640s, or what was really going on.

Now, the sort of Puritanism that Howard puts into this character is different, because Howard’s character, Solomon Kane’s a loner, a man who always fights for his own cause, but when he hears those almost voluptuous pagan stirrings in the background, it’s always Christianized, and it’s always put in a Protestant context.

Cromwell once had a phrase: “I disembowel you for Christ’s love.” And that’s what he said in the Putney Debates. When the parliamentary side won the Civil War, the whole New Model Army, which of course was a revolutionary army of that time—no brothels, no drinking; in the Royal army, you went to the back, and there was endless entertainment at the back of the battlefront. With the Puritan armies, there was none of that. You went to the back, and there was no drinking, and there was a chap ranting at you about whether you’d sinned that day.

It was less fun, but at the same time, when they raised their pikes together, not in a higgledy-piggledy way, or one bloke at the back didn’t want to, but they raised them together, as one unit. They would all chant, “God is our strength.” Cromwell understood as Shaw said early in the 20th century that a man who has a concept of reality that is metaphysically objectivist, a man who believes in something as absolute truth is worth fifty men. And that’s the type of revolutionary ideology that these people then had.

But at the Putney Debates, there was a debate about how the country should go, and Ireton and the other supreme commanders were there. Under Cromwell they committed regicide of course, they killed the King, so the future of the country was theirs. There was another tendency known as the Levellers, who in some ways of course were retrospectively the first socialists, so-called because they wanted to level down distinctions. There was an even more radical movement called the Diggers that came along later. But Cromwell told Ireton, “Either we hang them or they will hang us.” And that’s the Levellers. And at the end of the Putney Debates, the army moves aside, the Cromwellian regime has been established, and the Levellers are hanging on the trees. So Cromwell had got his way.

The importance of Protestantism to the United States, in a complicated way, is the reason why there has never been an extreme Right-wing movement of any great success in the United States, except in a localized way like the Klan to deal with particular circumstances at a particular time. America, you could imagine, is ripe for such a movement, as Australia always has been, and yet there has not been one, not really. Not a national movement. There were figures in the 1930s: there was the Silver Shirt movement; there were Father Coughlin’s radio broadcasts, which had all sorts of interesting ramifications in American life, as Catholic priest giving the radical Right to essentially a Protestant nation, which of course set up a cultural tension and contradiction in and of itself.

There are also interesting liberal counterparts to this. Most people remember Orson Welles’ treatment of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, when the Martians invade New York, and then he admitted it was a fiction retrospectively, and tens of thousands of ninnies leave New York because they think the Martians are landing. “Gee, they’re up the road!” And they get the pickup truck, and they go. And then they broadcast later that it was all a stunt and it was an artistic show, and people shouldn’t take it literally.

Welles deliberately did that to discredit Coughlin. He said afterwards, “We did it because too many people believed everything that fascist priest was telling them on the radio, so we proved them, don’t believe what you hear that comes out of the radio.” And that’s a purely sort of aesthetic response to the impact that sort of thing had.

Yet still movements lie there, Aryan Nations, National Alliance, these sorts of movements, very small, very isolated, geographically and in other ways. National Alliance was quite interesting because it morphed from Youth for George Wallace. That’s how it started, and then it took various transformatory steps until it emerged as a very hard-line group under the late Dr. William Pierce at a later date.

Yet still movements lie there, Aryan Nations, National Alliance, these sorts of movements, very small, very isolated, geographically and in other ways. National Alliance was quite interesting because it morphed from Youth for George Wallace. That’s how it started, and then it took various transformatory steps until it emerged as a very hard-line group under the late Dr. William Pierce at a later date.

And this culture of extreme Protestantism—which contained elements which are to the Right of almost anything you’ve ever seen, mentally, psychologically, conceptually—seems partly, because, of its extreme individualism, to be incapable of generating radical Right mass movements. Most Americans still adopt a deliberately materialist, liberal humanist and individualist way of looking at life. They divide into two basic political parties that have switched over during the course of the last two centuries. Don’t forget in the 19th century the Republican Party was the party of the nominal Left, and the Democrats were red. The Democrats were conservatives who supported states’ rights—not the right to secede, but certainly the right to own slaves. The party led by a man who’s proud to have ex-slaves in his own family, the present President, would have actually, in a strange sort of way, not been able to join the Democrat Party in the 19th century, and yet the switch around, that you can vote in each other’s primaries, and that “Isn’t everyone a Democrat? Isn’t everyone a Republican?,” hence the meaninglessness of the names, adds to this sort of feeling that you get in the contemporary United States that all that matters is money and social success. America’s very important, because America, of course, dominates this country now culturally and geopolitically. We can’t almost do anything without them, and all the wars that we’re now dragged into are due to American hegemony.

But the repudiation of parts of American power should never blind ourselves to the cultural excellence of what many white Americans have achieved, both for their group and individually. If you actually look at all the radical Right literature, the alternative side of an isolationist and American nationalist posture, there is some great work there by people like William Gayley Simpson, who wrote an enormous book of over a thousand pages called Which Way Western Man? Again, without going on a tangent too much, he’s a very interesting man because he’s an ex-Trappist monk. He began as a liberal and an aching humanist whose heart bled for the Third World and who had all the correct sort of UN-specific attitudes, and gradually he changed step by step by step, and he ended up, if not a member then a fellow traveler, of the National Alliance. That is quite a change. That is quite a leap. But it is also true that tens and tens of thousands of educated Western people who are liberal-minded now will have to change their views, will have to begin to change their mindset in this and the coming generation if Western civilization is virtually not to slide off the cliff. [. . .]

Now, to return to Howard, Howard’s writing, by the end of his sort of period, and don’t forget that he was sort of mature at 22 and dead at 30, he produced 160 stories, 15, 16 volumes basically, and other fragments. There was an unfinished fantasy novel called Almuric, the early Celtic stories, Bran Mak Morn and the others morphed into Solomon Kane. There were associated Westerns and humorous stories. There were some detective stories, but he never particularly liked that genre, although his attitude towards life was hard-boiled. There were also some Crusader stories as well, and some slightly mythological stories about a sort of white man in the East called Gordon, presumably named after the Gordon of Khartoum, but actually an American, and these were the old Borak stories set in Afghanistan, where he goes native and fights along sort of inter-tribal and group-based and clan lines in that context.

Howard’s attitude toward politics is quite complicated and not entirely logical, and primarily emotional. He supported the New Deal because he believed the American economy had collapsed and something needed to be done. He argued strongly with H. P. Lovecraft, he was more of a “reactionary” in these respects, a classical liberal, didn’t like the Roosevelt and the people around him, didn’t like intervention in the market in that sort of Protestant, American way. He felt that you fail commercially, you suffer punishment, because God has chosen that punishment for you. Destiny involves sacrifice.

The irony is that the banks have been saved in the United States by Bush, costing trillions of dollars, but the metaphysic which founded the country would have allowed all of those banks to fail, all of those banks to fail and all those bankers to hang themselves and throw themselves off buildings. That happened in 1929, and then you rebuild quickly, because the pure, American, sort of Randian view is that capitalism is an insatiable animal and vortex of energy, and if people go to pot, if people lose everything they have, if as a trader, an insurance agent I vaguely knew years ago at Lloyd’s, lost all his money in the Names scandal, and goes there on a Sunday and unlocks the door and goes down to the toilets and sits there and drinks Domestos and kills himself and is found by the cleaners, Africans probably, on Monday morning, and his senior partner in Lloyd’s said, “Well, that’s capitalism for you.” And that’s it! What goes up goes down! This was the view that founded the United States

And yet the irony is, why have these Western politicians intervened, why have they saved these structures: few collateral damage moments, Lehman Brothers; they’ve charged Goldman Sachs with fraud. Well, that’s a bit late, isn’t it, really? And yet why have they intervened? They’ve intervened because of the voting danger. The fact that there are radical parties on the fringe of all Western societies, everyone knows who they are, that people could vote for in a major moment of fiscal/physical/moral/emotional distress, and the whole Western clerisy that’s bought into the contemporary liberal package knows that. Many of these parties are actually quite moderate in relation to the traditions they come out of, but they terrify the present establishment that often sees the more populist ones as just the start of something worse that’s coming behind, see?

And there’s also a certain guilt there as well, because these people are well aware of what’s happened to Western societies because they’ve been running them for 70 years. This idea it’s all an accident, “I didn’t really mean it,” and the turning of Western societies into a sort of version of Brasília, en masse with a tiny, little elite at the top that’s creaming most of the goodies off for themselves.

I’m not an egalitarian in any sense, but it’s interesting to note that this country’s slightly more unequal now than it was in 1910 in terms of 90% of all equity and all capital and all wealth is owned by the top 10%, and the top 2% of that 10%, and yet the society has changed out of all recognition, 1910 to 2010. Most Western people born in the first [unintelligible] part of the 20th century would not believe the transformation of the West just in a lifetime, basically, after they died. And it occurred because of the extraordinary wars, largely amongst ourselves, that we fought in the 20th century that also gave outsider ideologies like Communism their chance to vulture-like pick over the defeat and the carrion corpses of what was left.

The heroic attitude towards man and society that Howard’s work depicts exists virtually nowhere except as play and pleasure in computer games for boys and adolescents, in comic books and so on. The areas of life where that sort of ethos remains, the armed forces, the army, navy, and air force of most contemporary Western societies, particularly their specialist or elite forces, in Britain the Special Air service, the naval equivalent the Special Boat Service, and all of those novels, these Andy McNab sort of novels about the heroic and this sort of thing, which are lapped up by a largely male audience, largely male audience. Other than that, there is not really the imprimatur of the heroic in Western life, the extraordinary demilitarization of Western life, hardly ever see a policeman, hardly ever see soldiers. When do you ever see British forces? And that’s because they’re always outside the country as globalist mercenaries fighting American and Zionist wars all over the world. They’re never seen here, and many of their commanders don’t want them here, either, because they regard parts of British life as so irretrievably decadent that they actually want to keep their troops away from much of what’s happened in relation to the society. There are towns in Berkshire where a lot of the military stay, like Arborfield and these sorts of towns, where it’s quite clear there’s a sort of military zone and there’s a civilian zone. You all know what British towns are like on Friday, Saturday night: no police; they’re all in their vans; they’re all in the station; they’re at home; they’re filling in forms. They wear yellow bibs when they’re out, but when you want one, you can never see them, can you?

And a lot of our older people are, let’s face it, frightened to go into town and city centers on Thursday, Friday, Saturday, certainly after 6. And why is this happening? It’s partly happening because the concept that Howard’s fiction deals with, masculinity, has been completely disprivileged, completely demonized and rerouted in contemporary liberal life. Hostility to masculinity, certainly as defined, say, before 1950 is very considerable, and it’s had a very corrosive effect ideologically, aesthetically. Men can have their own pleasures in various zones, which are sort of sneered at and disprivileged, but the centrality of the heroic as a myth for life has largely gone.

The way to explicate something like Howard, as I did with Lovecraft before, is to maybe to concentrate on one of their stories. With H. P. Lovecraft I chose “The Dunwich Horror,” and with Howard I would choose “Rogues in the House,” which was published in Weird Tales in the early ’30s. One fantasy critic has called it the greatest fantasy story of the 20th century, but that’s just one individual’s opinion. It’s relatively early in the Conan series.

Conan is a northern barbarian, and because everything’s fused together in Howard, he’s got slightly Nordic, Germanic, and slightly Celtic traits. He’s an outsider, but he has a clean code of masculine barbarism. Civilization is always seen as slightly weak-kneed and sybaritic to Howard. And yet at the same time, barbarism has its own inner order.

Now, there are counter-factual and countercultural elements there that will be used by social anthropologists in a totally different context, like Lévi-Strauss and others, in the middle of the 20th century, but Howard means it in a different way.

There’s a Left-wing streak to Howard, as there was to London, a siding with the outsider, with those ruined by capitalism, by tramps. London’s book about the East End is one of the most extraordinary books about mass poverty before George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London and “How the Poor Die,” were quite extraordinary works. A poor little hospital in Paris before any sort of socialized medicine, where those who were in the bottom 10%, their corpses were just thrown on the ground! And they died in agony, and they kick you away and put another one on top. This is how the poor die! And Orwell said to this chap in this hospital, “But look at the state they’re in!” And he said, “Well, they gave up slavery. Here’s another batch.” This was the attitude then. This is why things like the labor movement, even in the United States in an attenuated way, were created, to correct that imbalance as it’s seen from the bottom.

The far Right, of course, always wanted not the class war of the contemporary Left, but to socialize mass life in a way that preserved the traditions of the civilization of which we’re a part, that brought on what was excellent about the past and yet realized that the 50% of people who own no capital, the 50% of people who are largely excluded from all center-Right parties’ definition of patriotism, are part of the country, are part of the nation, fight the country’s wars for the most part when they’re asked to do so, and therefore have to be within the remit of social consideration in relation to education, health, and other matters.

My explanation for Howard’s support of the New Deal and that type of politics largely is along those sorts of lines. It’s the sort of apolitical chap who likes country and western in a Midwestern state and supports socialized medicine up to a point, as long as it’s not too costly, doesn’t like Obama, and supports our troops, you see. But it’s in a sort of apolitical zone which has got no real knowledge above that. Some of the instincts are right, but the ideological formulation in which that takes place is likely wrong, because even these wars—do you think Iraq was fought for ordinary white Americans? Do you think Afghanistan has anything to do with ordinary families living in Nebraska or Nevada or Kansas? None of these wars have anything to do with them at all. Even the Black Muslims have worked out that white gentiles largely are second-class citizens now in the society that they created. But that’s another story, and I’d just like to concentrate on Howard.

This particular story concerns Conan from the outside, Conan as perceived by an aristocrat and fop called Murilo. Howard’s a little bit of a Nordicist. He thinks southern Europeans are a bit foppish in comparison to northern Europeans. There’s a streak of this, and some of the society is seen to be Italy, Corinth, Zamora, but they’re not. But they seem to be Italy.

Well, there’s this Italian city-state that’s run by a corrupt priest called Nabonidus, who’s known as the Red Priest. These myths are set, these stories, mythologically encoded, are set before the beginning of recorded history and after the sinking of Atlantis, possibly a fantasy itself. So he sets them far back enough that he can do whatever he wants with them, but at the same time he can import a large amount of retrospective historical insight.

The interesting thing is the Machiavellianism of the politics of these stories. All of these societies are run extremely ruthlessly and are run completely for the power interests of the people in charge. The nationalities don’t really matter, but they are, if the gloves are off, as marauding and vengeful as their own leaders who they represent at a lower level. Truly Howard believes, with the Roman dictator Sulla, that when the weapons are out, the laws fall silent.

Now, Murilo is a courtier, a relatively corrupt courtier, in this city-state, and Nabonidus comes to him one day at a royal council meeting and gives him a small casket that contains a severed ear. And this is a warning, as it would be if a Renaissance prince in post-Medieval Italy, gave it to a rival, and it’s, “Clear off. Get out of the city-state as quickly as possible. I’m giving you one day.” And Murilo wonders what he’s going to do. He can flee, but he’s not a coward, why should he leave his own city? And in any case he’s got lots of rackets on the go, you know, so he wants an out, and he thinks, “I need to assassinate Nabonidus,” who runs the drunken King as a sort of priest/philosopher-king/leader of a native death cult within the city like a puppet master controls his dog.

So he needs a vassal, and he finds it in the prisons of the city where a young, heathen, northern barbarian has been captured and lays there in chains after various escapades and thefts, and this is a young man of 19 called Conan, who’s twice the size of a normal man. All Howard’s heroes are physically enormous, and all incredibly violent, although they all have an honor code of their own which is interesting, particularly towards the end of the story, what you might call an innate code of masculine morality and honor which is part and parcel of natural law.

The Social Darwinian view that was spread throughout mass culture, particularly these types of fictions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, is not entirely true as all prisons and all armies testify, there’s a code of honor and morality even in very extreme male behavior. Rapists are always amongst the most disprivileged in any prison. Men who attack and feed on women, for example, in very all-male and male-concentric cultural spaces are always disprivileged, always disliked, and that’s because of innate feelings about how, in a very traditionalist way, what we call partly a sexist way now, men should treat women, and these things pre-date all modern ideas and are partly innate, and in some ways, because Howard is such an instinctualist, he brings these sorts of forces to the fore.

Now, Nabonidus wants Murilo to leave the city. Murilo hires Conan to murder Nabonidus. Nabonidus is [unintelligible]. Conan is in his cell sucking some beef off a bone, and besides, Nabonidus is an upper-class priest—so why not murder him for money, he’s an adventurer?—so he decides to go with Murilo on this plot. As always with Howard, a synopsis never does justice to the sort of the lucid dreaming of the story itself. Howard always said that he was there and that Conan was next to him like an old soldier dictating his stories, some of which will be tall stories as well.

Now, Murilo then hears that Conan has been captured because the guard that he bribed to get him out of the prison has been arrested on another offense. Conan’s actually escaped in another way and joins Murilo later. Murilo, desperate, a Borgia without any sort of a family fortune decides to murder Nabonidus himself, so he creeps up to his fortified estate, which is on the edge of town, described in this Gothic way—it’s dark, it’s sepulchral, it’s moonlit, there’s an enormous dog that roams the grounds.

Remember Conan Doyle’s stories? There’s always this enormous mastiff that the villain has that roams the grounds to bring people down, but Watson shoots on Holmes’ behalf usually at the end. In The Hound of the Baskervilles, which is extraordinarily amusing because the hound is covered with phosphorous to make it glow in the dark when it races after some poor chap who’s looking back, terrified, on a sort of West Country moor, and yet phosphorous is so poisonous that, the dog licks itself all the time, one lick and its dead. But these stories are metaphorical. They’re extreme exercises in the imagination. They’re not concerned with these pettifogging details of which critics make too much.

Now, Murilo creeps into the garden and, horror of horrors, what does he find? He finds the dead body of the dog, and it looks as though it’s been savagely mauled in a way by something he doesn’t understand, by some weird thing or ape or monster. He then proceeds into the house and finds much of it wrecked. Nabonidus is nowhere to be seen, and one of his servants, Joka, has been murdered.

Suddenly he gets into the inner chamber of Nabonidus’ villa, which is modeled on a Renaissance palace essentially, and he sees the Red Priest, so named because he wears this red cowl, sitting on a throne, made of alabaster, and everything’s heavy and ornamental, a bit like those Cecil B. DeMille films from the ’30s, everything extraordinarily overdone and luxuriant. And he creeps up to Nabonidus to stab him, and the figure turns, and it’s a were-thing, or a monster, something of the imagination. It’s not human at all, simian rather than human. And Murilo faints, and then the story closes.

This story’s in three acts. Traditionally, like a lot of Western drama, like Dante’s Inferno, Purgatory, Paradise, you’ve got this three-pronged triadic element, the thesis, the antitheses, the synthesis at the end. So that’s the first part.

The second part is Murilo awakens in dungeons or interconnected corridors underneath Nabonidus’ house, manse, mansion. He crawls along a corridor and somebody hisses, and it’s Conan. He’s come into the house to murder Nabonidus because Murilo’s going to pay him, and because he’s a member of a cult that he dislikes and so on. Murilo scents his hair, like the young aristocrats of his era, and Conan’s senses are so acute that he detects that with his nostrils, and that’s the reason he doesn’t attack him in the darkness.

They both decide to, they swear loyalty to each other—don’t forget this is an oral culture where bonds and legal sanctions are expressed orally. Howard despised the element of modern life where people say anything they want just to get their own way at any particular time. In pre-modern, say Nordic societies, the oath or something which is given verbally with strength is as binding as any legal document ever could be, even more so.

Conan and Murilo proceed looking for Nabonidus. They come out into the body of the house, which as I said resembles just sort of Renaissance, Florentine palace, and they see Nabonidus stripped, semi-naked and wounded, in a neighboring corridor, and they wonder what has replaced him up inside the house.

And what has happened, as he in a dazed way explains once he returns to full consciousness, is that his servant, who’s this ape that he’s taken from one of the outlying countries in Howard’s imaginary kingdoms, has supplanted him as the master in the house. Howard, to a moderate degree, believed in science, believed in evolution, it was very much almost a cult then, as was eugenics, and Thak as he’s called, this ape-man who wears the red because he’s supplanted the human he wanted to supplant, has thrown his master, Nabonidus, into the pit and has seized control of the house. Thak sits, waiting for them to come out of the pit because there’s a bell underneath there in the pits that they’ve crossed, a trap basically, and he knows humans are down there, and he’s waiting for them.

Nationalists emerge. There’s an interesting political element here, because Nabonidus is a very corrupt ruler and has the King in his thrall, so nationalists of the city-state—you could be a nationalist and of a city-state because it was the unit of civilization essentially, and a country would be city-states federated together. Attempts to assassinate Nabonidus in a way that Murilo wanted to, Thak deals with them. The story fast-forwards in a very filmic way, because Howard is a visualizer. The male brain is visual and always thinks in images. And these sorts of stories are extraordinarily cinematographical in their nature and their forward, pumping lucidity.

Thak senses that they’ve come up from under the ground, and there are interesting pseudo-scientific elements. The Red Priest, Nabonidus is a scientist and a mage and a magician combined. It’s Religion and the Decline of Magic in some ways if you view it academically. He has this construction of mirrors whereby from one room you can reflect light through tubes that contain small mirrors, and it ends up being able to look into another room, so you can actually look round corners, and they can see Thak, and he can see them.

Because he needs to dispose of the bodies of the nationalists who’ve come into the house, Thak disappears for a time, and Conan and the others seize their chance, and they go up. Nabonidus becomes terrified when all the doors are locked and he can’t find the weapons they need to fight against his servant who’s turned against him.

In the end, Conan has to face off against Thak in this quite extraordinarily violent scene. Howard was one of the most brilliant writers of physical force and conflict between men in the 20th century. There’s little doubt about that. It’s so immediate you’re almost there and it is essentially visual. Conan and Thak have this clash-of-the-gods-type of titanic duel with each other, much like a scene from Homer basically, Hector before the walls of Troy. Thak is done down in the end, and Conan, half-dead, is saluted by Murilo.

Nabonidus then tries to betray both of them, and Conan does for him, really, with a stool. He whips up a stool and throws it into his head, and he falls, and all Conan can say is, “His blood is red, not black,” because in the slums of the city they said the Red Priest’s blood was black because his heart was black, and Conan’s a barbarian and a literalist, you see. “His blood isn’t black.”

There’s an interesting moment when Conan is helped by Murilo because he’s so hurt and wounded in the fight with Thak, and he pushes Murilo aside and says, “A man walks alone. When you can’t stand up it’s time to perish.” That’s not an attitude you heard from the Blair government too often, is it? These are pre-modern attitudes, you see. As somebody on Radio 4 would say now, “But that’s a dangerously exclusionist notion. What about the ill, what about the weak?” And of course in that type of barbaric morality, the strong look after the weak, but only in an assent of being and natural law which is codified on the basis of the morality of strength. That’s what those sorts of civilizations thought and felt.

And the other interesting thing is that he looks down on Thak, this sort of beast, sort of man that he’s killed, and he says, “I didn’t kill a beast tonight, but a man! And my women will sing of him.” And there’s two cultural views of these sorts of things. One is to regard them as remarkable pieces of creative imagination. There is other is to sort of laugh and sneer at them, and think that they represent old-fashioned values that we’ve thankfully gotten rid of, or moved away from.

The stories, with the exception of the Kane stories, are all pre-Christian in the most radical of terms, and yet pre-liberal and liberal secular, which of course in the modern West is what’s replaced Christianity. I would say that contemporary Catholicism is rather like the Protestantism of yesteryear, and Protestantism has become liberalism, and liberalism has morphed, strangely, without the Protestantism that gave it a moral compass, into a form of cultural Marxism, and that’s what we have now.

And yet Howard’s stories are very, very interesting and very dynamic and very much appeal to an imaginative element in certainly a lot of men. The belief in self-definition, the belief in the heroic as a model for life, the belief in strength but with an honor code that saves it from wanton exercise in strength without purpose, and the beliefs that one is part of even a tribe or a community.

In the stories, Conan’s a Cimmerian. He’s from a northern group. He’s always introduced, he’s only got one name, he’s so primal, he doesn’t have any other names. Conan. Like Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights, he only had one name. Heathcliff, he doesn’t need any other names. He’s just a force, you see? A force of the female imagination, which is what he is. And in a strange way, the way in which he’s described in that novel by Emily Brontë is very similar to the way Conan’s described, but Conan’s a bit more beefed out, a bit more muscular.

Many films have been made, many TV series have been made, there’s a Conan industry in the 20th century. What Howard would have thought of all that no one knows. He’s there, possibly on a slightly lower tier, but with Tarzan and Doctor Who and James Bond and these other iconic sort of mass popular fantasy figures. Yet in all of them, certainly in this sort of material, there’s a truth to experience, there’s a vividness, there’s a cinematographical and representational reality, and there’s a concern with courage, masculinity, and the heroic which is lacking from most areas of society, and there’s also an honor code, a primitive morality if you like, which goes with it and gives it efficacy and purpose.

The other thing which he differentiates in this type of literature is respect for the enemy. When Terre’Blanche was murdered, I noticed liberals on the BBC giggling and sort of laughing and thinking it was all a jolly joke. These are people who are against the death penalty and believe that murder’s a terrible infraction against human rights, jurisprudence, and all the rest of it. But the sort of cultural space that this work comes out of respects the enemy. Kills the enemy, respects the enemy, which of course is a soldier’s emotion. Many who’ve fought in wars don’t disrespect the enemy. They know what they’re like. British soldiers who’ve fought in the Falklands, American soldiers who’ve fought against Islamist militants, and even some of the militants themselves when they’ve fought against Western warriors, understand the code of the soldier and the code of the warrior on the other side. But many of these men are spiritually, fundamentally similar men in a way, born in other groups.

Men will always fight with each other, and they’re biologically prone to do so. How, in an era of mass weapons of destructive warfare, some existing and others not, that is to be worked through. It is a part of the destiny of the relationship between groups and states. But the hard-wiring that makes men competitive and egotistical and conflict-oriented is ineradicable and irreducible, and modern liberal societies which are based upon the idea of inclusionist love without thought of conflict are sentimental to the point that they will fall apart, bedeviled by their endless contradictions.

And I personally think that if you inculcate yourself, with a bit of irony and estrangement, from some of the elements of the culture of the heroic that certainly subsisted as mainstream cultural fare in our society before 1950, you have a different attitude towards what spews out of the telly every evening, and you have a different attitude towards the sort of culture that you’re living in, and you have a different attitude towards great figures in your own group and even in others, and you have a different attitude towards yourself and the future.

I give you Robert Ervin Howard, 1906 to 1936, a man who walked alone but spoke for an element, not just of America, but what it is to be white, male, Western, and free.

Thank you very much.

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/05/robert-e-howard-and-the-heroic/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/RobertEHoward2.jpg

[2] YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1ucBGENZjnM

[3] Pulp Fascism: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/04/forthcoming-from-counter-currents-pulp-fascism/

[4] editor@counter-currents.com: mailto:editor@counter-currents.com

00:07 Publié dans Littérature, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite anglaise, nouvelle droite britannique, jonathan bowden, littérature, littérature américaine, lettres, lettres américaines, robert e. howard |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 04 mars 2013

Lovecraft as Heideggerian Event

“A General Outline of the Whole”

Lovecraft as Heideggerian Event

By James J. O'Meara

Weird Realism: Lovecraft and Philosophy [2]

Winchester, UK: Zero Books, 2012

A winter storm in NYC is less the Currier and Ives experience of upstate and more like several days of cold slush, more suggestive—and we’ll see that suggestiveness will be a very key term—of Dostoyevsky than Dickens.

On a purely personal level, such weather conditions I privately associate[1] with my time—as in “doing time”—at the small Canadian college (fictionalized by fellow inmate Joyce Carol Oates as “Hilberry College”[2]) where a succession of more or less self-pitying exiles from the mainstream—from Wyndham Lewis and Marshall McLuhan to the aforementioned Oates—suffered the academic purgatory of trying to teach, or even interest, the least-achieving students in Canada in such matters as Neoplatonism and archetypal psychology.[3]

One trudged to ancient, wooden classrooms and consumed endless packs of powerful Canadian cigarettes, washed down with endless cups of rancid vending machine coffee. No Starbucks for us, and no whining about second-hand smoke. We were real he-men back then! There was one student, a co-ed of course, who did complain, and the solution imposed was to exile her—exile within exile!—to a chair in the hallway, like a Spanish nun allowed to listen in from behind a grill.

Speaking of Spain, one of the damned souls making his rounds was a little, goateed Marrano from New York, via Toronto’s Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, no less, who was now attempting to explain Husserl and Heidegger, to “unpack” with his tiny hands what he once called, with an incredulous shake of the head, “that incredible language of his,” to his sullen and ungrateful students.[4]

I thought of this academic Homunculus, who played Naphta to another’s Schleppfuss[5] in my intellectual upbringing, when this book made its appearance in my e-mail box one recent, snowing—or slushy—weekend. For Harman wants to explain Husserl and Heidegger as well, or rather, his own take on them, which I gather he and a bunch of colleagues have expanded into their own field of Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) or Speculative Realism. And to do so, he has appropriated the work of H. P. Lovecraft, suggesting that Lovecraft play the same role of philosophical exemplar in his philosophy, as Hölderlin does in Heidegger’s [3].

“That incredible language of his” indeed!

Part One tries to explain this Object Oriented business, but only after he tries to justify or excuse dealing with someone still often regarded as a glorified pulp hack on the same level with the great Hölderlin. He tries to short-circuit the attacks of highbrow critics, still exemplified by Edmund Wilson’s, by denouncing their rhetorical strategy of paraphrase.

Paraphrase? What’s wrong with that? Perfectly innocent, what? Well, no. Drawing on Slavoj Žižek’s notion of the “stupidity of content”—the equal plausibility of any proverb, say, and its opposite—Harman insists that nothing can be paraphrased into something else—reality is not itself a sentence, and so it is “is too real to be translated without remainder into sentences” (p. 16, my italics). Language can only allude to reality.

What remains left over, resistant to paraphrase, is the background or context that gave the statement its meaning.[6] Paraphrase, far from harmless or obvious, is packed with metaphysical baggage—such as the assumption that reality itself is just like a sentence—that enables the skilled dialectician to reduce anything to nonsensical drivel.

Harman gives many, mostly hilarious, examples of “great” literature reduced to mere “pulp” through getting the Wilson treatment. (Perhaps too many—the book does tend to bog down from time to time as Harman indulges in his real talent for giving a half dozen or so increasing “stupid” paraphrases of passages of “great” literature.)[7]

Genre or “pulp” writing is itself the epitome of taking the background for granted and just fiddling with the content, and deserves Edmund Wilson’s famous condemnation of both its horror and mystery genres. But Lovecraft, contra Wilson, is quite conscious, and bitingly critical, of the background conditions of pulp—both in his famous essays on horror and, unmentioned by Harman, his voluminous correspondence and ghost-writing—and thus ideally equipped to manipulate it for higher, or at least more interesting, purposes.

The pulp writer takes the context for granted (the genre “conventions”) and concentrates on content—sending someone to a new planet, putting a woman in charge of a space ship, etc.[8] If Lovecraft did this, or only this, he would indeed be worthy of Wilson’s periphrastic contempt. But Lovecraft is interested in doing something else: “No other writer is so perplexed by the gap between objects and the power of language to describe them, or between objects and the qualities they possess” (p.3, my italics).

Since philosophy is the science of the background, Lovecraft himself is to this extent himself a philosopher, and useful to Harman as more than just a source of fancy illustrations: “Lovecraft, when viewed as a writer of gaps between objects and their qualities, is of great relevance for my model of object oriented ontology” (p. 4).

Back, then to Harman’s philosophy or his “ontography” as he calls it. I call it Kantianism, but I’m a simple man. The world presents us with objects, both real (Harman is no idealist) and sensuous (objects of thought, say), which bear various properties, both real (weight, for example) and sensuous (color, for example). Thus, we have real and sensuous objects, as well as the real and sensuous qualities that belong to them . . . usually.

All philosophers, Harman suggests, have been concerned with one or another of the gaps that occur when the ordinary relations between these four items fail. Some philosophers promote or delight in some gap or other, while others work to deny or explain it away. Plato introduced a gap between ordinary objects and their more real essences, while Hume delighted in denying such a gap and reducing them to agglomerations of sensual qualities.

Harman, in explicitly Kantian fashion this time, derives four possible failures (Kant would call them antinomies). Gaps can occur between a real object and its sensuous qualities, a real object and its real qualities, a sensuous object and its sensuous qualities, and a sensuous object and its real qualities. Or, for simplicity, RO/SQ, RO/RQ, SQ/SO, and SO/RQ.

Take SQ/SO. This gap, where the object’s sensuous qualities, though listed, Cubist-like, ad nauseam, fail, contra Hume, to suggest any kind of objective unity, even of a phenomenal kind—the object is withdrawn from us, as Heidegger would say. It occurs in a passage such as the description of the Antarctic city of the Elder Race:

The effect was that of a Cyclopean city of no architecture known to man or to human imagination, with vast aggregations of night-black masonry embodying monstrous perversions of geometrical laws. There were truncated cones, sometimes terraced or fluted, surmounted by tall cylindrical shafts here and there bulbously enlarged and often capped with tiers of thinnish scalloped disks; and strange beetling, table-like constructions suggesting piles of multitudinous rectangular slabs or circular plates or five-pointed stars with each one overlapping the one beneath. There were composite cones and pyramids either alone or surmounting cylinders or cubes or flatter truncated cones and pyramids, and occasional needle-like spires in curious clusters of five. All of these febrile structures seemed knit together by tubular bridges crossing from one to the other at various dizzy heights, and the implied scale of the whole was terrifying and oppressive in its sheer gigantism. (At the Mountains of Madness, my italics)

SQ/RO? This Kantian split between an object’s sensuous properties and what its essence is implied to be, occurs in the classic description of the idol of Cthulhu:

If I say that my somewhat extravagant imagination yielded simultaneous pictures of an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature, I shall not be unfaithful to the spirit of the thing. A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings; but it was the general outline of the whole which made it most shockingly frightful. (“The Call of Cthulhu,” my italics)

SO/RQ? Harman admits it’s rare in Lovecraft, (and elsewhere, though he finds hints of it in Leibniz) but he finds a few examples where scientific investigation reveals new, unheard of properties in some eldritch or trans-Plutonian object.

In every quarter, however, interest was intense; for the utter alienage of the thing was a tremendous challenge to scientific curiosity. One of the small radiating arms was broken off and subjected to chemical analysis. Professor Ellery found platinum, iron and tellurium in the strange alloy; but mixed with these were at least three other apparent elements of high atomic weight which chemistry was absolutely powerless to classify. Not only did they fail to correspond with any known element, but they did not even fit the vacant places reserved for probable elements in the periodic system. (“Dreams in the Witch House”)

And RO/RQ? You don’t want to know, as Lovecraft’s protagonists usually discover too late. It’s the inconceivable object whose surface properties only hint at yet further levels of inconceivable monstrosity within. Usually, Lovecraft relies on just slapping a weird name on something and hinting at the rest, as in:

[O]utside the ordered universe [is] that amorphous blight of nethermost confusion which blasphemes and bubbles at the center of all infinity—the boundless daemon sultan Azathoth, whose name no lips dare speak aloud, and who gnaws hungrily in inconceivable, unlighted chambers beyond time and space amidst the muffled, maddening beating of vile drums and the thin monotonous whine of accursed flutes. (Dream Quest of Unknown Kaddath)

You can see, in each case, how the horrific effect, and the usability for Harman’s ontography, would entirely disappear if given a Wilsonian “paraphrase”: It was a squid with wings! The object, when analyzed, revealed new, hitherto unknown elements!

Confused yet? Bored? Don’t worry. The whole point of Harman’s book, to which he devotes the vast portion of the text, is analyzing passages from Lovecraft that provide vivid illustrations of one or more of these gaps. In this way Harman’s ontography acquires its Hölderlin, and Lovecraft is rescued from pulp purgatory.

While there is considerable interest in Heidegger on alt-Right sites such as this one,[9] I’m sure there is considerably more general interest in Lovecraft. But Harman’s whole book is clearly and engagingly written, avoiding both oracular obscurity and overly-chummy vulgarity; since Harman is admirably clear even when discussing himself or Husserl, no one should feel unqualified to take on this unique—Lovecraftian?—conglomeration of philosophy and literary criticism.

The central Part Two is almost 200 pages of close readings of exactly 100 passages from Lovecraft. As such, it exhibits a good deal of diminishing returns through repetition, and the reader may be forgiven for skipping around, perhaps to their own favorite parts. And there’s certainly no point in offering my own paraphrases!

Nevertheless, over and above the discussion of individual passages as illustrations of Speculative Realism, Harman has a number of interesting insights into Lovecraft’s work generally. It’s also here that Harman starts to reveal some of his assumptions, or biases, or shall we say, context.

“Racism”

Harman, who, word on the blogs seems to be, is a run-of-the-mill liberal rather than a po-mo freak like his fellow “European philosophers,”[10] tips his hand early by referring dismissively to criticism of Lovecraft as pulp being “merely a social judgment, no different in kind from not wanting one’s daughter to marry the chimney sweep” (“Preliminary Note”). And we know how silly that would be! So needless to say, Lovecraft’s forthright, unmitigated, non-evolutionary (as in Obama’s “My position on gay marriage has evolved”) views on race need to be disinfected if Harman is to be comfortable marrying his philosophy to Lovecraft’s writing.

His solution is clever, but too clever. Discussing the passage from “Call of Cthulhu” where the narrator—foolishly as it happens—dismisses a warning as coming from “an excitable Spaniard” Harman suggests that the racism of Lovecraft’s protagonists[11] adds an interesting layer of—of course!—irony to them. As so often, we the reader are “smarter” than the smug protagonist, who will soon be taken down a few pegs.

But this really won’t do. Lovecraft’s protagonists are not stupid or uninformed, but rather too well-informed, hence prone to self-satisfaction that leads them where more credulous laymen might balk. “They’s ghosts in there, Mister Benny!”

Unfortunately for Harman, Lovecraft was above all else a Scientist, or simply a well-educated man, and the Science of his day was firmly on the side of what today would be called Human Biodiversity or HBD.[12] Harman may, like most “liberals” find that distasteful, something not to be mentioned, like Victorians and sex—a kind of “liberal creationism” as it’s been called—but that’s his problem.

It would be more interesting to adopt a truly Lovecraftian theme and take his view, or settled belief, that Science, or too much Science, was bad for us; just as Copernicus etc. had dethroned man for the privileged center of the God’s universe, the “truth” about Cthulhu and the other Elder Gods—first, there very existence, then the implication that they are the reality behind everyday religions—has a deflationary, perhaps madness inducing, effect.

Consider this famous quotation from the opening of “The Call of Cthulhu” as quoted by Harman himself in Part Two:

The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but someday the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

Thus Harman could argue that HBD may be true but bad for us to know—something very like the actual position of such liberal Comstocks as Richard Lewontin.